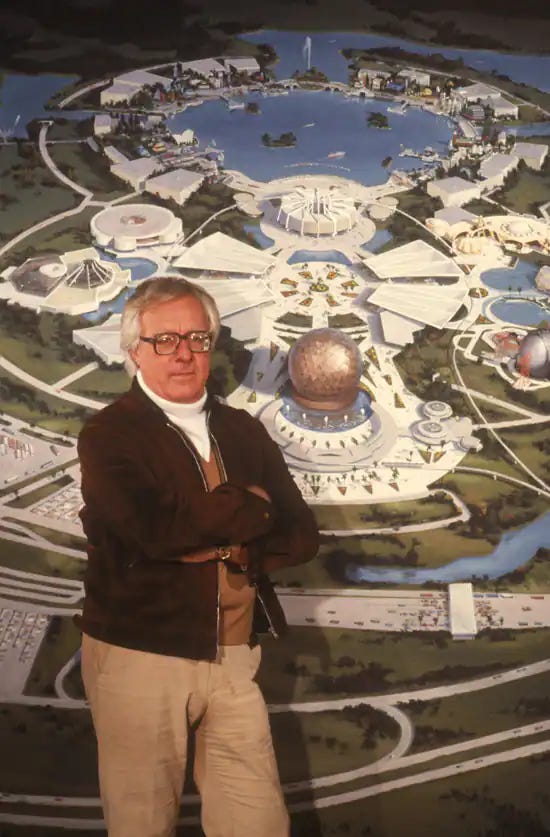

Author Ray Bradbury with a rendering of EPCOT Center.

Is Disney apocalyptic?

Your first impulse here might be— “what?!?” In contemporary English, apocalypse evokes an ending, or end-times— and often, a cataclysmic one. Fire, brimstone, monsters, gaping hellmouth, etc.

But the original Greek of this term means an “uncovering.” Sometimes it is an uncovering or revelation about the future. It can be a good future, or a bad one.

And Disney is most definitely about futures.

During the final years of Walt Disney’s life, he developed a friendship with prolific science fiction writer Ray Bradbury.* In later years, Bradbury—who died in 2012— consulted with Imagineering on several projects, particularly EPCOT.

Referring to EPCOT, Bradbury said, “Everyone in the world will come to these gates. Why? Because they want to look at the world of tomorrow.”

It’s an almost biblical image. In many narratives and poems of the Hebrew bible, the gates of a city were more than a physical portal. They were a place of judgment, or a place of prophecy, or a place of wisdom. A place where tribes (or armies) might gather. Later, in the Christian New Testament, gates are associated with the “New Jerusalem” in the book of Revelation (aka the Apocalypse of John).

I don’t mean, of course, that either Disney theme parks or films can fit literally in the ancient genre called “apocalyptic,” which predates the New Testament but is specific to Jewish, Christian, and some other religious and philosophical texts of the ancient Mediterranean and West Asian regions.

But EPCOT in particular is about beginnings and endings—or, in religious language, creations and redemptions.

It began in the 1960s as a proposal for the “City of Tomorrow” (or Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow— “city” and “community” were lobbed back and forth in early concepts). Some of our final images of Walt Disney are from a promotional film on “The Florida Project,” for which this working city was to be a centerpiece.

Then, in December 1966, Disney died. The Florida project began— as planned—with another theme park. EPCOT was eventually resurrected as a permanent World’s Fair (another inspiration for EPCOT), with tourists and employees—but rides, rather than residents.

Ray Bradbury wrote the early scripts for EPCOT’s signature ride, “Spaceship Earth.” “The Future has many arts, many sciences, many paths, many doors,” he wrote in one draft.

In other words, many gates.

**

Even when visions of the future are optimistic, they remake the world, by design. In a speech commemorating the tenth anniversary of Walt Disney World, Bradbury said:

“Walt and his bright noon fancies stand alone in a wicked world and say: Let’s ‘Do Everything Over and Do It Right.’”

That part sounds pretty darn apocalyptic to me. We’ve mucked it all up. Time to tear it down and begin again.

In the next breath, he declared: “Walt says terrible things like, Joy, Smile, or We Guarantee the World Won’t End Tomorrow.”

So Bradbury’s vision of Disney is paradoxical. It offers a fresh beginning without any endings.

And this is where childhood comes in.

The symbol of the child—not actual living, breathing, children, who are, let us remember, people— is about the future. In scholarly and theological terms, childhood is teleological (from “telos”— “end”). Because it is assumed they will grow up—in the future— adults often see children as tiny redemptive time capsules, bundles of possibility to send forward and build anew. To build a world the adults may not live see.

But Disney’s magic is how it promises adults they will see this world with their children. For a time, the “Spaceship Earth” attraction featured a song called “Tomorrow’s Child” (not written by Ray Bradbury). “Tomorrow’s child, shining a brand new way,” went the chorus. “For the future world is born today!”

And that was the point of early EPCOT (and still is the point of many Disney experiences). If you were an adult who brought your offspring to EPCOT in the 1980s or 1990s, you exited this marquee attraction— a history of human communication sponsored by AT&T, from cave paintings to the brand-new-in-1982 home computer— and exited into “Future World.” You got to be in a freshly born New Jerusalem with your children, right away, via Disney magic.

You didn’t just have to imagine the wonderful world in which they would live after you died.

You got to walk in through the grandiose gateway of the geosphere yourself, and join them.

**

Next week I’m traveling to a seminar about—guess what?— the end of time! Please bear with me as both my summer course, my summer writing, and my summer work responsibilities are making newsletters a bit less frequent. Still here! And a hearty welcome to my new readers—thanks for finding me.

*What Ray Bradbury, author of one of the most famous tomes about book censorship, might say about Florida (and the US) today is… a different but important letter.